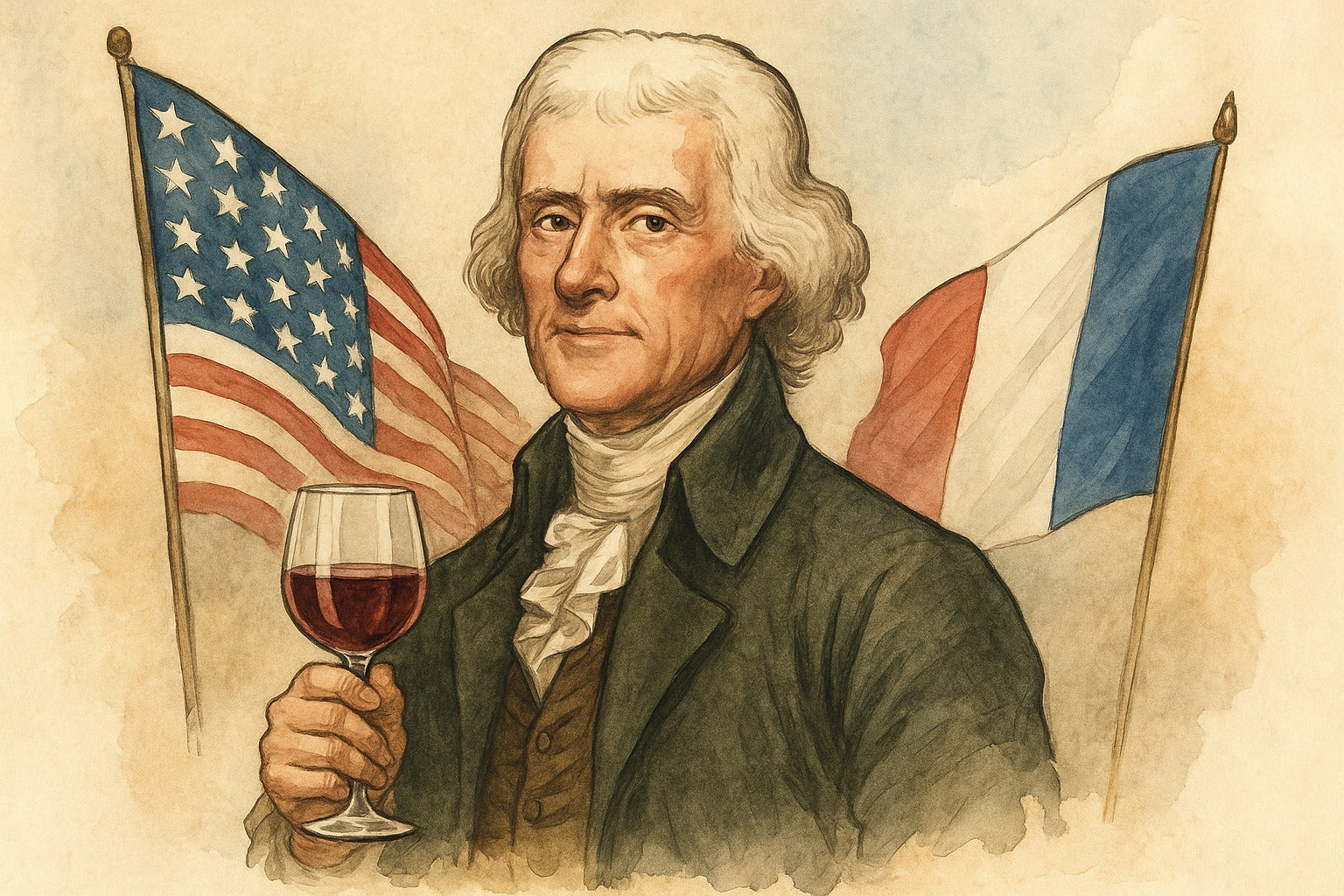

Thomas Jefferson walked so our sommeliers could run

Let’s rewind to the 1780s. America was still licking its Revolution wounds, and Thomas Jefferson—yes, that Jefferson—was off in France, technically serving as a diplomat. But while he was supposed to be building alliances, the man was also busy doing something far more important: drinking wine. A lot of it.

Jefferson didn’t just dabble. He toured Burgundy, Bordeaux, and the Rhône like a man on a mission. He took notes. He knew his Chambertin from his Volnay. He geeked out over Haut-Brion, Lafite, Latour, and Yquem long before they were investment pieces. And here’s the kicker—he wasn’t doing it just for the flex. He actually believed Americans deserved better wine. Wine as culture. Wine as refinement. Wine instead of the gut-punching grain alcohol most people were chugging back home.

He even tried to change policy for it. Jefferson argued that wine should be cheaper, taxed less, and celebrated more. Because, in his own words: “No nation is drunken where wine is cheap; and none sober, where the dearness of wine substitutes ardent spirits.” In other words—give people good wine, and they’ll stop blacking out on bad whiskey.

But here's where it gets more interesting. Jefferson didn’t just fall in love with French wine—he tried to recreate it. He shipped bottles back to the U.S., he planted vines at Monticello (RIP to that idea), and he set the tone for what American wine lovers would eventually chase: not just flavor, but story, place, craft.

Now, fast forward a couple hundred years.

French wine still dominates the myth. Burgundy and Bordeaux still hog the spotlight. But the Jefferson playbook? It's very much alive. Sonoma, Napa, Oregon—places where winemakers don’t just make wine, they question the rules. They experiment, they fail, they try again. They build something that doesn’t rely on centuries of tradition or a label in cursive. And they make wines that would’ve made old TJ raise a glass and say, “Hell yeah.”

So yes—this July 4th, we’re raising a glass to independence. But not just the kind written on parchment. The kind you can taste. The kind that doesn’t need a French passport or a noble surname.

Because at the end of the day, Jefferson wasn’t just sipping Burgundy to feel European. He was trying to figure out how Americans could drink better—boldly, honestly, freely.

And that’s a revolution we can still get behind.

Drink Different. Or Die Bored.

Cheers,

Bruno

Share:

Pinot‑Gate: The $7 Million Syrah in Disguise

“I’m Not Drinking Any F*ing Merlot”